Moment of the Month April/May 2022: Food, Framing, and Freedom

Changing the Language and Approach to Addressing Food Apartheid & Celebrating Good Food News

Perhaps two of the most well-known, wide-ranging, and difficult to overcome social and environmental factors that impact health are oppressive forces (like racism) and barriers to basic needs (like healthy foods).

Both are parts of people’s lived experiences that are at once private and personal but also consistently brought out into the public spotlight for debate and decision-making often without the consent or input of those most directly affected.

Because of this, these issues quickly become calls to action.

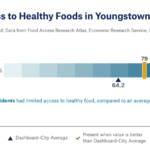

There are many concerning numbers, lists, and rankings lining up data and directing our community partners and leaders to do something in response. It stings each time one of these data points is read or heard no matter how many times or how much time has passed in between. Focusing on food, here’s how the Mahoning Valley stacks up—

- The Youngstown-Boardman Metropolitan Statistical Area is the 2nd most food insecure MSA in the country. [Source: FRAC 2018 “How Hungry Is America?” Report]

- 1 in 5 adults live 2 or more miles away from healthy food [2018 Mahoning & Trumbull Counties Community Health Assessments]

- Only 1 in 4 adults are consuming the recommended 5+ servings of fruit and vegetables per day [2018 Mahoning & Trumbull Counties Community Health Assessments]

- Nearly 3 in 4 adults reported a weight status that is considered overweight or obese [2018 Mahoning & Trumbull Counties Community Health Assessments]

Data and numbers are important when looking at the impact of an issue like food insecurity, but there’s another layer to consider: language. During a recent conversation about the importance of language in naming problems and shaping solutions, members of the Partnership’s Healthy Food Retail Action Team compared common terms used to describe the broad issue of food insecurity. Terms examined included:

What came out of the dynamic discussion is that any conversation or proposed solution to improve access to healthy foods must first acknowledge larger questions about why and how we’ve found ourselves with so many barriers between people and something so basic to our individual and collective survival as nutrient-rich foods. Very few individuals or communities have control over food production and distribution. Most people and communities have come to rely overwhelmingly if not exclusively on large, disembodied corporations (from farms, to distributors, to retailers, and so on) to feed themselves and their families. This profound disconnect impacts communities of all shapes, sizes, and geographies–from rural villages of a couple thousand residents to urban metropolitan areas home to several million.

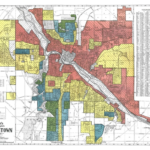

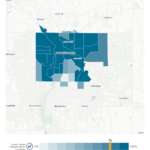

Recognizing this increasing disconnectedness between food and families is important, but peeling back the next layer of the onion reveals the role of historic practices and policies like redlining and restricting the movement and access to opportunity of Black people and people of color. Redlining, as defined by the New York Times, is: “racial discrimination of any kind in housing, but it comes from government maps that outlined areas where Black residents lived and were therefore deemed risky investments.”

Though the practice of redlining ended on paper with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the impacts are still felt throughout the country and our communities to this day. As was recently reported by Jennifer Rodriguez from WKBN, the practice of redlining and restricting access to quality, affordable housing and financial resources continues to reverberate in numbers like the percentage of Black residents who experience economic barriers–lower wages, more hurdles in place to accumulate wealth, etc. Since there is a direct link between housing, neighborhoods, economic and educational opportunities, and health, if you look at the 1938 Redlining Map for Youngstown and then use the City Health Dashboard mapping tool for Youngstown to search various health datasets (like food insecurity), you can see the ghost of this practice show up in the present. While the practice has largely stopped, the effects of redlining continue to linger.

All of this is important to understand the complexities of an issue like food insecurity—or food apartheid, a term that more accurately accounts for the imbalance of power and agency—and the shift towards food sovereignty, which, according to the US Food Sovreignty Alliance, is: “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

The language we use to engage with each other and our communities matters, and it can (and should) change over time as we learn and grow together. The Greater Pittsburgh Community Foodbank provides a brief but powerful summary of their evolution from fighting “food deserts” to eliminating “food apartheid” and why that shift in language, thinking, and acting matters:

The T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies, however, points out that the word ‘desert’ creates thoughts of ‘a barren landscape devoid of life, vibrancy and abundance’ (Lu, 2020). We know that this is not true of any communities we serve, including the now 20 neighborhoods that Green Grocer visits each week. Malik Yakini, a Detroit food activist, notes that the individuals who live in so-called food deserts likely would never refer to their communities in this way, as it is a term “imposed by outsiders”. He adds that the term could, intentionally or not, ignore the successes and history of a community and only focus on what it does not have.

So, what should we call neighborhoods that lack access to fresh foods and grocery stores, to no fault of their own? A food apartheid is more than the lack of grocery stores and other healthy food options in non-white and/or low-income communities. Food apartheid also points to the discrimination of communities of color when it comes to economic opportunities. The T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies notes that solutions must address economic disparities. Putting grocery stores in these communities cannot be the only solution. It must start with equity across the board – job creation, education and other opportunities in areas that have traditionally been ignored.

There are several food focused initiatives that have kicked off in the last two months that are attempting to change the framing and the narrative about barriers to food access. Those leading these efforts are creating more space for new leadership and partnerships to identify solutions to these challenges that center the people and places that have been impacted by problematic policies like redlining.

Below are brief descriptions of each effort with photos and video to highlight and celebrate the beginning of what will most assuredly be a long but prosperous journey towards bringing food justice to the Mahoning Valley.

Glenwood Fresh Market

- Lead Partners: Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation

- Funding Partners: Mercy Health Foundation of Mahoning Valley, The HealthPath Foundation of Ohio, United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program COVID Relief and Recovery

- Project Description: The Glenwood Fresh Market provides year-round access to FREE fresh fruits, vegetables, and other healthy food items to residents of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley. The market also provides free health screenings, nutrition literacy courses, cooking demonstrations and other resources to members. Residents can become members if they are a household living under 200 percent of Federal Poverty Guidelines or a SNAP recipient.

- Press Clips: Fresh Market in Youngstown Making Positive Impact on the Community | Glenwood Fresh Market Serving Thousands

- Glenwood Fresh Market

- Glenwood Fresh Market | Ribbon Cutting

- Glenwood Fresh Market

- Glenwood Fresh Market | Ribbon Cutting

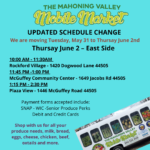

Mahoning Valley Mobile Market

- Lead Partners: ACTION, Flying High, Inc.

- Lead Funding Partners: Community Foundation of the Mahoning Valley, the Youngstown Foundation, the Western Reserve Health Foundation, the William Swanston Charitable Fund, the city of Youngstown and Mahoning County

- Project Description: From the Business Journal: “The Mahoning Valley Mobile Market is an innovative approach to provide healthy foods and nutrition to the area’s most vulnerable populations. A portion of the fruits and vegetables will be grown at Flying High’s greenhouse at the Campus of Care in Austintown. Kitchen, prep and packaging work will also performed there at organization’s access building. Flying High personnel will stock the truck – about the size of a small bus – with fresh fruits and vegetables on one side of the aisle and frozen meats and dairy products on the other side. Consumers are able to pay with debit or credit cards, vouchers, or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) cards.”

- Press Clips: ACTION revs up mobile market for Mahoning| Mobile Market to Roll Out Next Month

- Mahoning Valley Mobile Market

Healthy Community Store Initiative Outreach Events

Seed Giveaway & Urban Wellness Markets (Mahoning County)

- Lead Partners: Mahoning County Food Access Coordinator, Intentional Development Group, Northeast Homeowners & Concerned Citizens Association, McGuffey Centre – Associate Neighborhood Centre

- Lead Funding Partners: Western Reserve Health Foundation

- Project Description: The Community Store Initiative seeks to partner with business owners of small, local stores to bring healthy foods and opportunities for overall wellness into neighborhoods. The Urban Wellness Markets and Seed Giveaways are outreach strategies to make plants and healthy foods visible and accessible to more people. The Initiative is guided by principles rooted in racial equity and lifts up the voices and values shared by Black people and people of color.

- Upcoming events include a summer growing and gardening series (see flyers below).

Healthy Community Store Event (Trumbull County)

- Lead Partners: Trumbull County Food Access Coordinator, Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership

- Lead Funding Partners: Trumbull Memorial Health Foundation, Finance Fund Healthy Food for Ohio

- Project Description: From the Tribune Chronicle: “TNP [and the Trumbull County Food Access Coordinator have] been addressing food access insecurities through the Healthy Community Store Initiative to help store owners connect with fresh produce distributors. This effort has served to expand relationships between food distribution companies and store owners within the area.

- Press Clips: Warren Store Adding Fresh Produce through Grant Funded Program

- Mahoning Food Access Seed Giveaway

- IDG Mahoning Food Access Initiative Gardening 101 Courses

- IDG Mahoning Food Access Initiative Gardening 101 Courses Marie participating in Gardening 101 Workshop