ICYMI Mahoning Matters | “For the Health of It”

On mushrooms and movements: Transformation starts underground

It’s almost officially summer. Memorial Day has come and gone, flagged by ceremonies to remember and honor service members who bravely sacrificed their lives for our country and by plenty of picnics to celebrate the fact that life continues to march on.

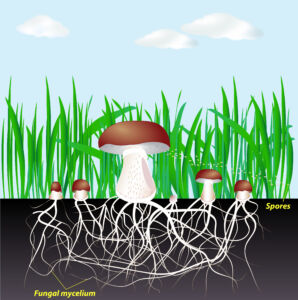

The natural cycles of life and death and hope resonate lately, especially this time of the year, as life reawakens in beautiful and brilliant ways. Flowers stand proudly upright in their beds. Trees shake out their leaves. All kinds of winged things are darting around, buzzing and chirping and singing the songs of the season. And, maybe an overlooked but no less vital part of the ecosystem, mushrooms and fungi begin to tip their caps as they pop up to say hello.

proudly upright in their beds. Trees shake out their leaves. All kinds of winged things are darting around, buzzing and chirping and singing the songs of the season. And, maybe an overlooked but no less vital part of the ecosystem, mushrooms and fungi begin to tip their caps as they pop up to say hello.

It’s always exciting to see spring’s first fungi while wandering through the woods, especially because mushrooms are among the forest’s most misunderstood but most influential members. Though they deal directly with the dead, decaying, discarded parts of the woods, mushrooms and other fungi play critical roles to create and clear pathways for new life to emerge. Because of mushrooms’ diligent yet discrete hard work, the lifeless is transformed into the life-giving. Supporting these natural cycles are essential for a healthy environment to grow and thrive.

During a recent discussion that sought to find a way to accurately articulate the intricacies of transformational change in our community, mushrooms were presented as the metaphor of choice. When I heard that, I immediately felt connected to the truth of the analogy and could not think of a better way to describe what large-scale, long-term social change looks and feels like. And, here’s an example to illuminate this illustration.

Naming the Problem

Two years ago, the world felt like it was going to swallow itself whole if it didn’t tear itself apart first.

The then-nascent COVID-19 pandemic was spreading fear, uncertainty, and pain throughout our communities. The tragic murder of George Floyd inspired protests and a surge of civil unrest in communities large and small, urban and rural that were crying out for justice and healing.

Connecting these topics was the growing recognition–and corresponding condemnation– that not everyone was experiencing the global pandemic in the same way, that injustices, inconsistencies, and inequities were seen and experienced more and more as time wore on. Many studies, including those recorded and reported by the US C.D.C. revealed that, Black and brown communities were and continue to be disproportionately impacted not only by COVID-19 but also the virus’ many adjacent and related consequences.

Two years later, the ongoing fallout from the over 1 million lives lost coupled with the rollback of pandemic aid programs like the expansion of benefits like SNAP (which has been a tremendous lifeline for children, college students, and older adults) and growing challenges for communities to provide quality, safe, affordable housing to all residents do not inspire much hope for a better, brighter tomorrow.

To solve a problem of any size or complexity, first it must be named. It needs to be called out and communicated to others so that solutions can be created to address it.

In the fevered pitch of 2020, local governments, health departments, agencies, and organizations across the country issued resolutions naming the problem contributing to the aforementioned challenges imposed on Black and brown communities because of the pandemic, ongoing violence, and the circumstances surrounding all of the above: racism was named as a root cause for these public health crises.

According to Ideastream Public Media, in Ohio “at least 27 cities and counties in Ohio have declared racism a public health crisis. Ohio boasts the second-highest number of municipalities that have passed declarations, according to the American Public Health Association (APHA).” Two of those 27 communities include Youngstown and Warren here in the Mahoning Valley. Both communities passed resolutions in June 2020.

What Now?

A lot has happened in the twenty-four months since these resolutions were passed making the naming of racism as a root cause for health disparities even more relevant. But, what’s the resolve like now? What progress has been made? What work has been done to break down and transform our organizations and our systems from life-taking to live-giving?

The act of naming racism (or racial inequities), especially as it survives (though often unintentionally) through institutional policies and practices, as a source for ongoing harm in our communities is a critical first step. But it is just that: a first step, one of many. Shortly after the ink dried on the resolutions, an inspired group of committed individuals and organizations came together to create the Mahoning Antiracism Justice and Inclusion Coalition, or MAJIC, to begin building a vehicle to put theory into practice and ideas into action. Members of MAJIC shared information about upcoming events, training seminars, and tools to help individuals and organizations become more intentional and impactful in efforts to become more equitable.

However, there was quickly a recognition that more structure and support were going to be necessary to truly move from intention to impact. Led by Mahoning County Public Health, a proposal was developed for where and how to access the resources needed to make that move.

Shortly after the resolutions declaring racism as a public health crisis were made, Mahoning County Public Health engaged with the Board of Mahoning County Commissioners in a dialogue about the need to invest resources to show there’s real resolve behind these resolutions to reduce health disparities and address racial inequities.

In July 2020, the Board of Mahoning County Commissioners issued a resolution of their own stating that the “Mahoning County Board of Commissioners desires to assist the Board of Health in pursuing programs designed to strategically reduce and eliminate the long-term impact of [health] disparities caused by social determinants in public health outcomes.” And subsequently, Mahoning County’s Board of Commissioners authorized a financial contribution of $72,813 to hire two consultants to help inform, support, and guide what would soon be known as the Vibrant Valley Health Equity Project to accomplish these goals.

The two consultants helping Mahoning County Public Health and Vibrant Valley are:

- Junious Williams , Senior Advisor at FSG Social Impact Company, who serves as an advisor to Mahoning County Public Health and Vibrant Valley to sustain a coalition using a collective impact framework with a health equity focus and to implement a project plan.

- Environmental Collaborative (ECO) provides capacity to Mahoning County Public Health in the areas of program management of Vibrant Valley, data collection and analysis, community engagement and preparation of project documents.

Getting to Work

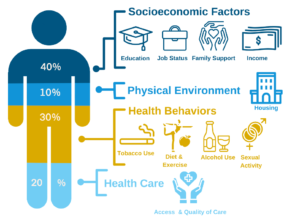

Because of Mahoning County Public Health and the Youngstown City Health District’s leadership, Vibrant Valley has become a collective, collaborative effort among public agencies and community partners to fully understand how our community is affected by social and environmental factors that impact health and to create a plan to specifically address inequities causing health disparities. These social and environmental factors like employment, neighborhood conditions, education, and oppression, overwhelmingly impact our ability to live full, healthy, prosperous lives, accounting for between 50-60% of an individual’s overall health outcomes.

Because of Mahoning County Public Health and the Youngstown City Health District’s leadership, Vibrant Valley has become a collective, collaborative effort among public agencies and community partners to fully understand how our community is affected by social and environmental factors that impact health and to create a plan to specifically address inequities causing health disparities. These social and environmental factors like employment, neighborhood conditions, education, and oppression, overwhelmingly impact our ability to live full, healthy, prosperous lives, accounting for between 50-60% of an individual’s overall health outcomes.

Vibrant Valley’s approach to exposing and ultimately eliminating systems and conditions that allow health inequities to continue is absolutely ambitious and absolutely necessary. The group has been meeting regularly and diligently for nearly a year–strengthening connections, reviewing data, and setting goals. And more importantly, Vibrant Valley has been laying the groundwork, breaking down barriers, and fertilizing the soil, metaphorically speaking, to allow new ideas, practices, and policies to sprout and spread.

Hours and hours of dedication have been poured into examining current organizational structures, practices, policies, and plans to see which of these elements advance equity, especially racial equity, and which get in the way. These conversations have been powerful and profound though they’ve not yet resulted in headline news. The underground work to nurture a network and framework for sustainable, transformational change is still being developed.

In this short time, partners are asking better questions and processes are being re-evaluated to make sure that equity, especially racial equity, is at the center of decisions being made. The update to Mahoning and Trumbull Counties’ Community Health Improvement Plan has made equity a regular part of the conversation and prioritization strategy, and other planning processes are following this lead. However, such an intentional focus on equity can reveal which parts of traditional community engagement processes have been problematic to ensure equitable access and impact. As is the case in many situations, uncovering blindspots or gaps is rarely a comfortable exercise, but as was already stated, you can’t solve a problem until it is seen, heard, and named.

Now Back to the Forest

Back to the forest. Mushrooms and their underground mycelium networks that supports them are perfect representations to describe what work centered on systems change, like Vibrant Valley, looks and feels like because:

- You will have to get your hands dirty and dig deep.

- A lot of the difficult work happens in the quiet, out of sight before it’s ready to break above ground.

- There must be a tight-knit network committed to working together in order for anything to happen.

Though there is still rightful urgency to visibly and completely eliminate racial disparities in health and everywhere else, there’s value in taking the time to do this kind of ground work. To make sure new systems are in place that are rooted, connected, and supported by partners throughout the community. Otherwise, the fragile, hollow structure built without enough support or a solid foundation will almost assuredly collapse and disappear.

As we approach the two year anniversary of our sibling cities in the Mahoning Valley recognizing the impact of racial injustice, racial inequity, and racism on residents’ ability to live full and healthy lives–and prepare for national (and local in Youngstown and Warren) celebrations of Juneteenth, it is important to take a moment to mark progress. To see what’s old, what’s new. How far we’ve come and how far we’ve left to go.

Though a new coalition, still learning how to stand and walk together, Vibrant Valley is committed to tackling issues and challenges to justice and equity that are unfortunately timeless. And, just recently there has been additional commitments from the City of Youngstown and the Board of Mahoning County Commissioners at $150,000 each to ensure Vibrant Valley’s efforts can continue to grow and flourish.

The individuals and organizations involved are not afraid to look and listen for inspiration from sources closest to the roots, like mushrooms, and embrace the methodology of the mycelium—to work closely together, often in the background, to sift out root causes for inequities, and to break down old, expired practices and policies in order to make way for fresh, new opportunities to take hold.

This sacred cycle of destruction, construction, and creation is also timeless. Much like we can count on the mushrooms to transform rotting organic material into rich soil to support new growth and life, we can count on coalitions like Vibrant Valley to create the conditions for our communities to one day grow and blossom to their fullest, brightest, and best potentials.

This is an updated version of the community column as published on Saturday, June 18, 2022.

Read “For the Health of It” every month at MahoningMatters.com