Stories of Systems Change: Mushrooms on Toast

A Tale of Enduring, Positive Change in the Mahoning Valley

Jessica Romeo, Mercy Health Community Health Educator, leads a healthy cooking demonstration at an Urban Wellness Market

Jessica Romeo served mushroom toast to intrigued customers visiting the urban wellness market hosted by a small store on the south side of Youngstown. A store that some would derisively call a “corner store,” because from the outside it looks like just another outlet focused on selling cigarettes, liquor, lottery tickets and junk food.

But the store and the mushroom on toast that Romeo, a community health educator with Mercy Health in the Mahoning Valley, served are small examples of an ongoing transformation occurring in the Mahoning Valley as more neighborhood merchants are acting as “community stores,” and more residents rely on them for access to food that is both healthy and a vehicle for deeper relationships.

Romeo served the toast as part of the Mahoning Valley Community Store Initiative supported by the members of the Healthy Community Partnership, which is a collaborative effort to reverse decades of individual and institutional decisions and practices that have resulted in the residents of Trumbull and Mahoning counties having some of the worst health outcomes in Ohio. The Community Store Initiative is one of a handful of efforts supported by the Partnership that facilitate access to healthy food within one mile of where people live. Others include mobile markets, farmers markets, and a food co-op.

The Community Store Initiative is not just another program designed by health professionals to encourage people to eat healthier. It was designed by the members of the Partnership, who include residents, health professionals, planners, food advocates, philanthropists and business owners. They designed it with the following core principle in mind: Isolated programs are insufficient to achieve the type of change needed for Valley residents to live healthy, thriving lives. The Partnership strives for deeper change. The initiative is designed to alter how individuals and institutions in the Valley think about their roles in their communities, the relationships they have with others and the power they have and how they use it.

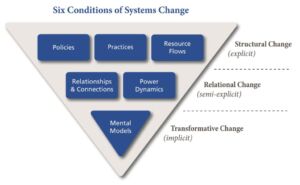

The social scientist’s term for the type and level of change that the Partnership’s members are pursuing is “system change.” The term reflects the multiple, inter-related factors that shape health outcomes in the Valley. Those factors, referred to as the “social determinants of health,” go beyond a person’s individual choices and include the quality of the neighborhood and built environment where an individual lives, their economic stability, and their access to health care.

Altering the social determinants of health requires multiple efforts, not a single program. Most importantly, those efforts need to be developed from the beginning with a deeper level of change in mind.

Changes in how we think, who we engage with and how we make decisions together results in improved resource allocations, policies and programs. A new program that is based on the belief that people who aren’t eating healthy need to be told what to eat will look much different than a program that is based on understanding those individuals in the program’s relationship with food. The Partnership’s approach to developing new programs is to first examine the deeply held beliefs and assumptions that may be contributing to the current state; identify what relationships need to be built and strengthened to develop and implement an effective program; and assess how power will be shared and exercised to sustain the program. Changes in how we think, who we engage with and how we make decisions together result in changes in better decisions related to how we allocate resources, design policies and implement programs.

Sophia Buggs, Director of the Mahoning County Food Access Initiative, building community and leading a garden education class in Youngstown.

Sophia Buggs, a dynamic force who plays multiple roles in the Valley and in the Partnership has a simpler language to describe the change she and her colleagues are advancing: “We need more community.”

Buggs leads the Community Store Initiative in Mahoning County, with an emphasis on neighborhoods in Youngstown. She’s also a farmer, educator and a passionate advocate for how food unites and empowers us. The Community Store Initiative authentically builds community. And a strong community is a healthier community. The urban wellness markets curated by Buggs bring together purveyors of fresh food, cooking demonstrations, yoga instructors, coffee roasters and others that are committed to engaging with merchants and residents. Buggs curates about a half dozen markets a year on land adjacent to community stores. “The markets build relationships with the owner, the residents and the land,” Buggs said.

The south Youngstown store wasn’t even open yet when Buggs began to engage with the owner, who had big dreams for the store but not a lot of experience. Buggs offered technical assistance to the owner and, as she does with all the merchants she works with, she explored whether the owner was interested in understanding and serving the community, or just selling products.

Buggs says the store is “in a neighborhood where it’s easier to catch a gun” than it is to access healthy food. Romeo was excited by the opportunity to share her passion for fresh food with the store’s customers, so she bought some locally grown shiitake mushrooms and fresh bread from a local bakery to prepare at the market.

Carlos Hilton, owner of Gene’s Market (a Community Store) in Youngstown, courageously trying mushrooms on toast.

Buggs smiles as she recalls how the store’s owner was so impressed by the flavor of Romeo’s creation that he called over some of his friends and encouraged them to try the unusual fare. Weeks later, when Buggs revisited the store, the owner asked if she could help him bring back “the woman with the mushroom toast.”

The merchant started selling fresh produce provided by Buggs to learn what products residents wanted. New customers were attracted to the store. Enough customers to justify installing a small cooler used to keep produce fresh.

“Food is community,” Buggs declares. She credits Romeo’s eagerness to engage with individuals as she prepares the food. She is building relationships, not just preparing food. “People aren’t just buying the food, they’re buying it for the joy that the food brings,” Buggs said.

What brings joy to some brings different emotions to others. And that’s OK. Food is no different. Romeo is fond of encouraging people to simply try one bite of what she’s prepared. “There’s a garbage can right there, you won’t offend me if you spit it out,” she assures the curious.

Lydia Walls and Matt Martin of Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership in one of the Trumbull County Community Stores | Photo from the Business Journal

Buggs, Romeo and the others involved in the effort’s design shaped and implemented it to shift the deeply held beliefs of both residents and merchants. Those deeply held beliefs include that selling healthy foods is unprofitable and that healthy food doesn’t taste good or is too expensive.

Buggs and her counterpart in Trumbull County, Lydia Walls, who works for Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership, another member of the Partnership , engage with merchants to better understand their motivations. Walls said it’s difficult to persuade some merchants to consider selling healthy food. But she has found plenty of merchants who see themselves as part of the neighborhoods they serve and are willing to experiment to better serve those neighbors.

“They have power in their neighborhoods,” Buggs said of the store operators. “They know they can help or hurt their customers’ health.” Buggs and Walls help the merchants use that power to help.

Merchants are willing to take the risk of trying new products, in part because of the unusual features of the initiative. Much like Romeo’s approach encouraging people to try a bite, take a taste before committing, Buggs and Walls engage with merchants to overcome their fears or preconceptions. The healthy food is provided to merchants for free, enough to taste and try it out. If it doesn’t sell, merchants are encouraged to use the food to feed themselves and their families.

Fresh produce restocked at one of Trumbull County Community Stores through a partnership with Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership and Central State University.

Walls concedes that the ideas they bring to the merchants don’t always work. She said in some neighborhoods, residents aren’t interested in healthier options and the owners are just trying to stay afloat. But the program is designed to allow for constant experimentation. If fresh produce doesn’t sell, then maybe healthier snacks will. And if that doesn’t work, Walls will keep listening, learning and suggesting different ideas.

The freedom to be patient, try things, and learn from mistakes is unusual for a program that is funded by philanthropic grant dollars. Often such grant-funded programs are guided more by the constraints of the grant than the needs of those the grant is meant to serve.

Romeo says with deep gratitude, “My organization gives me the freedom to throw ideas against the wall to see what sticks.”

And things are starting to stick. In January 2021, 7 stores were actively involved in the initiatives in the two counties. By the beginning of 2023, that number more than doubled to 15. As the programs become more established, new stores are able to look to other successful stores and be inspired to try healthier options. Stores that have been selling produce for several years now no longer require the same hand-holding process, allowing the coordinators to expand their capacity and reach new stores. While a few stores have bowed out, Trumbull County has seen six new stores join the program since early 2021.

Numbers alone cannot capture the shifts in mindset, relationships, and power dynamics that result from the collective effort. And the change goes well beyond the behavior of residents and store operators.

For example, Sarah Lowry, director of the Partnership, says the program’s innovative design reflects the commitment by the funders of the program to shift their approach to act as partners in the initiative rather than only as grantmakers.

Buggs values that unusual partnership. She is still learning the dynamics and dos and don’ts of seeking grants, completing grant forms, and fulfilling grant commitments. She credits Casey Krell, director of supporting organizations and donor services for the Community Foundation of the Mahoning Valley, for always being eager to listen and help. Krell’s stepping away from the traditional role of a funder brings her closer to the people seeking funding. “She is part of the community,” Buggs said.

Too often institutions “survey” the community more than they “serve” the community. Buggs sees the community foundation and the Partnership as serving the community, in the same way she serves the community by building authentic relationships rooted in the kitchens and the gardens of the Valley.

Shari Harrell, president and CEO of the Community Foundation, said the approach reflects a core element of the foundation’s new strategic plan to work with the community. Working with the community alters a more traditional power dynamic of the not-so-healthy version of the golden rule, the one that goes: The one with the gold rules.

Shifting power dynamics pervades the work of the Partnership. Buggs points to one act that altered her understanding of the power she has to catalyze positive change in her community. Lowry visited Buggs in her garden and asked her to join the Partnership’s Steering Committee.

She said she knew from the moment she was asked that the invitation came from Lowry’s heart, not to check a box to comply with some requirement.

Buggs was accustomed to advocating for healthy food that can be grown in our yards and gardens. But she was also accustomed to not being invited into rooms where decisions about health and food policy and practices were being made. Lowry helped her be an effective voice inside such rooms, which are usually dominated by credentialed professionals paid to be at the table. That the Partnership compensated residents like Buggs to participate in the meetings helped get her to the table. More importantly, it was clear that she belonged at the table because her perspectives, experiences, and ideas were valued. So much so that when it came time to expand the Community Store Initiative to Mahoning County and Youngstown, Buggs applied and was hired to lead the effort.

Sarah Lowry (front right) and Sophia Buggs (front left) smiling after a day in the Healing Garden in Youngstown.

As an individual, Buggs had poured much of her heart and soul into advocating for healthier food. She said her work with Lowry and the Partnership marked the first time anyone had ever poured energy and power back into her.

The initiative was designed not by a grantmaker or even the Steering Committee of the Partnership, but a work team that consisted of residents, healthy food advocates, business owners and others. Lowry said the design process was more deliberate, and likely slower, than if an outside expert in the field had designed it for the partnership. The group learned from early efforts at Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership and the Partnership provided additional resources that allowed TNP to enhance its initiative.

“The priorities were always relationships and quality, not product and quantity,” Lowry said. The Partnership wanted quality relationships with residents and store operators, as well as quality products. “If it was just a numbers game, we wouldn’t have taken the time to build trust and the initiative likely would have faded away. By taking the time to build those relationships we can experiment and learn and sustain the work over the long term.”

Buggs and Walls have built deep relationships with residents and merchants. Health professionals like Romeo and foundation leaders like Krell are more deeply engaged in the communities their institutions serve.

Power is being shared more and exercised differently. Buggs has learned: “There are enough of us that, when we speak with one voice, we are heard by those with power.” And increasingly, residents, merchants, funders, policymakers and service providers are thinking differently about food and their community.

“The mindset that is shifting is that food is not locked up somewhere inaccessible, it’s everywhere. It is in your yard. It is in the community store,” Buggs said. And if food is everywhere, then community is everywhere. And as that community grows and builds, there is confidence that health will be everywhere, too.